Behind every scar lies a story of pain, resilience and ultimately, triumph. For thousands of Nigerian women battling obstetric fistula (a devastating childbirth injury marked by continuous leakage of urine or faeces), these scars tell stories of lost dignity, abandonment and eventual rebirth through free surgical repair and empowerment.

May 23, observed globally as the International Day to End Obstetric Fistula, brings renewed attention to a condition that disproportionately affects impoverished women in Nigeria’s rural communities.

Yet even in the shadows of stigma, a movement is rising, powered by survivors, health workers and coordinated government action to ensure these women are repaired but never broken.

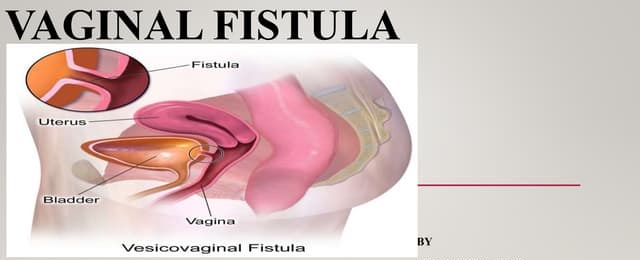

Obstetric fistula occurs from prolonged, obstructed labour without timely medical intervention. It causes an abnormal opening between a woman’s birth canal and bladder or rectum, leading to chronic incontinence. In Nigeria, where healthcare access is uneven, UNICEF estimates that over 400,000 to 800,000 women are living with untreated fistula, with about 13,000 new cases annually.

For an anonymous 23-year-old from Bauchi State, the trauma began immediately after childbirth. “I didn’t know what was happening to me. After delivery, I couldn’t control my urine,” she said. “The smell made people avoid me. My husband abandoned me. I hid myself for years.” Her isolation, like that of thousands of others, reveals a brutal intersection of poverty, gender inequality, and broken health systems.

Another survivor, just 17 years old, remembered the overwhelming joy of waking up to dry bedding after her successful obstetric fistula repair surgery. Married and living in rural Gombe State, she endured nearly a year of stigma, whispers and self-imposed isolation due to the constant leaking of urine and the sharp odour that followed her everywhere.

Her life changed in 2024 when a community health worker linked her to the National Obstetric Fistula Centre in Ningi, Bauchi State, through a special repair initiative supported by the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA). She had developed the condition after three days of obstructed labour at a poorly equipped health centre in Yamaltu Deba local government area. A desperate episiotomy was performed, but the baby didn’t survive. The young mother was left with both physical trauma and unbearable grief.

“I used torn wrappers as pads and changed them more than eight times a day, but the smell was still there,” she said. “At the mosque, people would move away. At weddings or naming ceremonies, they avoided sitting near me. Eventually, I stopped attending any gathering. My mother and younger sister were my only support.”

Thanks to the NHIA’s support, she underwent successful surgery in early 2024. The 14 days she spent at the centre were transformative. Alongside other women, she received health education, psychosocial support, and vocational training, including tailoring, soap-making, beadwork and embroidery. Some were selected to receive startup empowerment packs, complete with a sewing machine, fabric rolls, thread and sewing essentials.

“I used to feel like my life was over. But now, people call me ‘Hajiya Mai Dinki’—the woman who sews. I have found a new purpose and my dignity,” she said.

In June 2024, the Nigerian government, under the leadership of its Minister of Health & Social Welfare, Prof. Muhammad Pate launched an ambitious Fistula Free Programme to eradicate the condition by 2030. Jointly implemented with NHIA, the programme ensures that women receive not only free fistula repair but also transportation, feeding and post-operative counselling.

As of January 2025, the programme has recorded significant progress. A total of 2,160 surgeries have been performed across 18 centres of excellence in nine states. Additionally, 1,137 women have been enrolled in the NHIA scheme, ensuring ongoing access to maternal and reproductive healthcare. Another 1,901 women have benefited from family planning services, reducing the risk of recurring fistula. Notably, the surgical repair of vesico-vaginal and recto-vaginal fistulas has achieved a success rate of over 80 per cent.

Health workers on the front lines have noticed the change. A nurse in Gombe said, “Before NHIA came in, women had to buy their drugs or wait for donations. Now, they are treated with dignity—without paying a kobo.”

For one woman from Katsina, the journey was even more daunting. “In December 2023, I went to Tanzania for surgery. It failed. I lost hope. But in 2024, I was referred to Katsina’s fistula centre through the Fistula Free Programme. Today, I’m healed. I walk with pride.”

Others, like another survivor once ostracised for the smell of incontinence, now help other women seek treatment. “I was ignored. But today, I am like everyone else. I help women like me find hope.”

Physical repair, however, is just one part of the healing. Emotional scars from years of exclusion linger. That is why post-surgery reintegration, through psychosocial support and vocational training, remains critical.

In Gombe State, over 50 women have been enrolled in training programmes and provided with startup kits for tailoring, soap-making, and small trade. One 22-year-old said, “When I left the hospital, I didn’t just return home, I returned as a tailor. I now train others. I’m not a burden anymore.”

This holistic approach, which combines surgery, mental health support and economic empowerment, is now being replicated in Bauchi, Kebbi, Katsina, and other states.

The programme’s success leans heavily on strategic alliances between the Federal Ministry of Health, UNFPA, NHIA, the Government of Norway and committed local institutions. UNFPA supports over 3,000 free repairs annually, supplies surgical kits, conducts stigma-reduction campaigns and provides manuals for health workers.

In 2020, UNFPA and the Federal Ministry of Health launched Nigeria’s National Social and Behaviour Change Strategy for the Elimination of Obstetric Fistula (2020–2024), a blueprint for combating stigma and raising awareness.

With nearly 40 per cent of the world’s obstetric fistula cases in Nigeria, these partnerships are not just helpful; they are essential. Yet despite progress, Nigeria still ranks third globally in obstetric fistula burden.

Challenges persist: early marriage, poor rural health infrastructure, inadequate emergency obstetric care, cultural taboos and a shortage of trained surgeons. A urogynaecologist in the FCT observed, “Fistula is not just a health issue. It’s a reflection of systemic failures from education to access to emergency care. Until we fix those, the condition will remain.”

Other challenges include cultural silence, limited awareness in remote areas, and poor referral systems. Countries like Malawi, Ethiopia, and Uganda face similar challenges, making cross-country learning critical.

“We must learn from each other,” the doctor added. “Prevention, early detection and reintegration must be community-led and country-owned.”

Every repaired fistula is a restored life. Every empowered survivor becomes a voice for the voiceless.

As one survivor put it, “I thought I was forgotten. But today, I know I matter. I am not broken. I am whole.”

To end fistula in Nigeria, it will take more than surgery. It will require political will, sustained donor investment, stronger health systems, and collective compassion. Most of all, it will require listening – truly listening – to the women behind the statistics.

Because healing a woman is healing a nation.